Lifelong resident Joe Abbin said there is a simple way to reduce crime in Albuquerque and that is to put more police on the street and more criminals behind bars.

“We have quit arresting and prosecuting,” Abbin told New Mexico Sun.

Albuquerque crime rates have been exponentially greater than the national average and climbing during the past 10 years. According to data pulled together by Abbin from the FBI Unified Crime Reports, violent crime rates in Albuquerque in 2020 were 346% of the national average. The same data shows property crime rates were 256% of the national average.

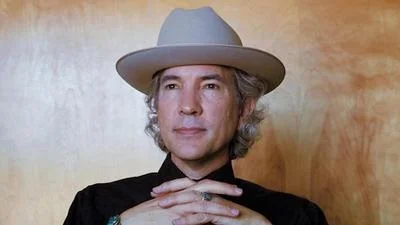

Joe Abbin

| Facebook

Abbin is an author who has studied law enforcement statistics and reports, a subject he has spoken about them many times. But his insights are boosted by another aspect of his career. He was a reserve police officer for 36 years.

“I served under 12 different chiefs and I served with over 300 different officers as partners on the street,” Abbin said.

Abbin was 78 when he retired in early 2020. At 80 he has thoughts on how Albuquerque can reduce its crime rate and make the city safer for its residents.

“Why are we so bad? Answer: We have more criminals on the street,” Abbin says in a presentation he offers. “Why so many criminals on the [Albuquerque] streets? Answer: They are not in jail. Albuquerque is in a crime crisis. What can citizens do? Answer: Be informed, protect yourself, keep the pressure on our elected officials, vote.”

He said the city needs to hire more police officers — it is supposed to have a force of 1,000 but is well short of that number — and needs to prosecute more cases and incarcerate more criminals once they’re convicted. Those are short-term solutions.

He said the Albuquerque Police Department was seriously affected by a court-approved settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice in 2015 over complaints about excessive use of force.

“Between 2010 and 2015, the city paid out millions and millions of dollars for wrongful death and excessive use of force, and Department of Justice determined that the Albuquerque Police Department had a culture of aggression,” Abbin said. “I was on the police force during that period, and most of the officers, the vast majority, actually didn't use any more force, including myself, than was needed to do the job.

"Some use of force is just part of the job in many cases," he added. "But we had officers that, I believe, were out of control in the city and [whom] the department did not manage properly.”

He said that caused a reluctance to arrest or pursue people for low-level crimes, including shoplifting, vandalism, prostitution or crimes that affected quality of life, such as littering, trespassing and public nuisances. In addition, the number of inmates that could be held was reduced as incareration facilities were deemed inadequate. That meant more criminals were on the street, not behind bars.

Add in a shortage of investigators, prosecutors and lab technicians, inadequate case preparation by police officers causing more plea deals to be struck, and what Abbin views as excessive use of diversion courts. He said these measures are fine for first-time offenders, 90% of whom don’t commit another crime, but are much less successful with repeat offenders, as only 10% remain out of legal trouble.

He said a bail reform movement largely eliminated the use of bail and pretrial detention in 2016. The result has been “disastrous,” he said.

Abbin said law enforcement can’t solve these problems alone.

“Long term, we need cultural change and legislation to address mental illness, homelessness, poor parenting, illegal aliens, addiction, poverty, poor education and rehab in and out jail,” he says in his presentation.

Abbin is a supporter of the broken windows policing theory, which holds that visible signs of disorder create more disorder. He said it was very effective in New York City.

“Absolutely," he said. "Our own statistics, our eye on that material that you got use of a 10-year history there, and you can see that between 2010 and 2013, for instance, we have twice as many people in jail and we had half the major crime rate. I know we've illustrated that broken windows works. We used to arrest for virtually everything like shoplifting, as an example.”

Critics have said this law enforcement system unfairly targets minorities. Abbin rejects that.

“I'd say it’s bogus,” he said. “The reason being is, unfortunately, people of color are the majority of our street criminals. I don't know why? That's kind of a thing for the sociologist to study, but we have, for instance, among the blacks in general in the United States, they constitute 14% of the population. They commit 50% of the homicides.”

Abbin notes that black and Hispanic communities overwhelmingly favor strong police presences in their neighborhoods.

“Yes, indeed,” he said. “And they are for far more aggressive policing because it turns out they are also the major number of victims. There are groups that seem to make a living off of the police and claiming discrimination. But the black community and the brown community, too, for that matter, are in favor of more aggressive policing.”

Abbin is the author of the book "ABQ Blues — Crime and Policing in Albuquerque, NM,” one of five books he has written in addition to numerous magazine and newspaper articles. He is the former chairman of the Foothills Community Policing Council.

He was recently interviewed by Bernalillo County Sheriff Manny Gonzales, who is running for mayor of Albuquerque. When asked about the differences he’s seen since his time working with the local police, Abbin mentioned a change in policing tactics.

“In the middle of a major crime wave in Albuquerque [that] we’ve been in there four years, now, ranked in the top five in the country, our jail’s half empty. That doesn’t make sense,” he said.

In a previous interview with New Mexico Business Coalition, Albuquerque mayoral candidates Tim Keller and Gonzales were asked about their approach to rising crime rates in Albuquerque.

Gonzales mentioned a three-point solution involving leadership, depoliticization, and cultural changes at the department. Keller referenced more than $30 million in technological updates that he supported for the police. Those updates, he said, have made it possible for property crimes and auto thefts to drop, despite violent crime rates rising.

Abbin said when he retired in 2020, he was the oldest police officer in the city — by far.

“But I could still do all the agility, the training and the shooting, and I've been blessed," he said. "I was sick a lot when I was a kid. But for some reason in my later years here, I've had remarkably good health and I set a new bench-pressing personal record two years ago. I lifted more than I did in competition when I was 22 and 32 and 42.

“Isn't that something? Like I said I've been blessed, and I never intended to stay on the police department that long, but I felt like I was doing something good,” Abbin said.

He said most of the officers were much younger than him, but they got along well and learned from each other.

“They're young and they were actually very encouraging to me," he said. "I loved working with them. I was, of course, more mature and had a lot more life experience. And I had a lot more experience working with people because I've been a businessman. I was employed by Sandia Labs and was in middle management for 30 years. But the young guys, they were better on the paperwork and on the computer. So we worked well together.”

He said he experienced many things, including some rough moments as a sworn officer.

“Oh, I was involved in many fights,” Abbin said. “Never shot.”

He is a lifelong resident of Albuquerque who earned bachelor and master of science degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of New Mexico in 1964 and 1966. Abbin worked for Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque from 1964-1994, working and in and managing activities related to nuclear weapons, national security, and energy systems.

After retiring from Sandia, he founded Roadrunner Engineering, specializing in the analysis, design, and sale of high-performance equipment and books for automotive applications.

Abbin has kept busy as a registered professional engineer and holds five U.S. patents.