Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists have found a way to avoid certain science fiction book and movie plots by using a technique to better estimate stress in earth’s crust from oil and gas drilling.

In a study published last month in Nature’s Communications Earth and Environment journal, the scientists reported a way to estimate stresses that can be endured in the earth’s crust without a traditional borehole analysis or studying historical earthquake data.

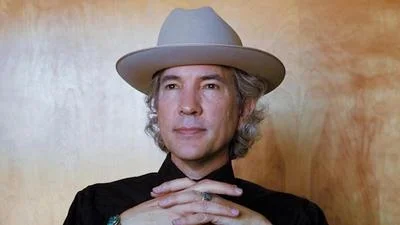

Los Alamos National Laboratory Research Geophysicist Andrew Delorey

| lanl.gov/

"The orientation of maximum horizontal compressive stress can be estimated by inverting earthquake source mechanisms and measured directly from borehole-based measurements, but large regions of the continents have few or no observations," the study said. "Here we present an approach to determine the orientation of maximum horizontal compressive stress by measuring stress-induced anisotropy of nonlinear susceptibility, which is the derivative of elastic modulus with respect to strain."

Applying the report's findings and recommendations could reduce costs when trying to determine whether a proposed oil and natural gas drill could cause earthquakes, in addition to predicting in which direction fractures are likely to occur during hydraulic fracturing.

The study's lead author, Los Alamos Research Geophysicist Andrew Delorey who studies nonlinear elasticity, told The NM Political Report that the study stemmed from an idea the team had to look at why rocks become softer or stiffer when under horizontal compression occurs beneath the earth's surface. The compression causes fractures that open or close, based on how fast seismic waves pass through the rocks.

"So, in other words, does a wave that's traveling south to north behave the same as going east to west," Delorey said in the NM Political Report news story published Friday, Oct. 15.

The study considered whether a rock would have different properties "when you look at it, from different directions," Delorey continued. "And when we discovered that they did, then we tried to do more work to see why the behavior is different in different directions. And we realized that it was aligned with the stress field."

Following that observation, the team tried to determine whether the behavior was just a coincidence or do always rocks get softer or stiffer as they align with a stress field.

"And it turned out that where we measured it, it was always aligned with their stress field," Delorey said.

As an additional benefit, the study's suggested testing method would cost 10 to 20% less than a borehole analysis, Delorey said.