Purgatory may not be something all people believe in, but to Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, Mexican actress Lupe Vélez, indigenous interpreter La Malinche, and La Llorna, a fictitious, forlorn woman, the intermediate state between life and death comes to life in Living Purgatory, a play penned by Patricia Crespin and directed by Alicia Lueras Maldonado.

Written for her Master’s thesis at the University of New Mexico, Crespin’s play is a poignant tale on how recklessness leads to rebirth and loss leads to liberation.

When Denise, a drug-addicted mother and her baby Allegra (a Latin word meaning lively), arrive in Purgatory, the women there bond to get baby Allegra back to the land of the living.

The actors conducted a passionate rendering of the play In a staged reading held at the National Hispanic Cultural Center, performed as a “drama of redemption.” To restore the baby, “The women must face the reasons for their own damnation and confront the sins that bind them to Purgatory.”

The sin all women share is that they discarded their children, disposed of life. As dour as the subject is, the play had delightful moments, spawned by its fiery dialogue.

Over the entire reading, I sat engaged by its cross-cultural symbolism, with nods to both Dante and Aztec lore. The play accomplishes what is described as a “profound exploration of … self-forgiveness … and the devastating power of guilt.”

Concerning guilt, the National Library of Medicine defines it as “the awareness that one has performed, might perform, has been, or could be the beneficiary of an action or inaction that has caused or could cause harm or inequality to befall another party …” Guilt can lead to grief. And in the play the women exhibit both traits.

Philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand, in his book The Art of Living, suggests that guilt is connected to a lack of reverence for others. A guilty person is one who ignores the objective value of another human being, mistreating or ignoring them. The solution, according to Hildebrand, is reverence. With reverence, “people…take a position…that…enables them to grasp values,” to recognize our common humanity.

The duo of adverse feelings—guilt and grief— is at the heart of Living Purgatory, asking how do humans find redemption amid regret?

For Frida Kahlo it’s compassion.

For Denise it’s understanding.

For Lupe Vélez its self-validation.

For Malinche it’s restoration.

For La Llorna it’s forgiveness.

In other words, the women vie for virtuous values, helping Denise—and her miraculous child— find what they’ve lost: life, desire amid the dread. As the Frida Kahlo character states, “Everything has beauty, even the worst horror.” And like the mint plant mentioned throughout the play, the women seek the purification of healing hands.

In a world plagued by suffering—both personal and public—it’s delightful to find a work that holds out hope to the hurting, restoration for the remorseful, and a reminder of the reverence for life.

To learn about more events at the National Hispanic Cultural Center, go to: https://nhccnm.org/events.

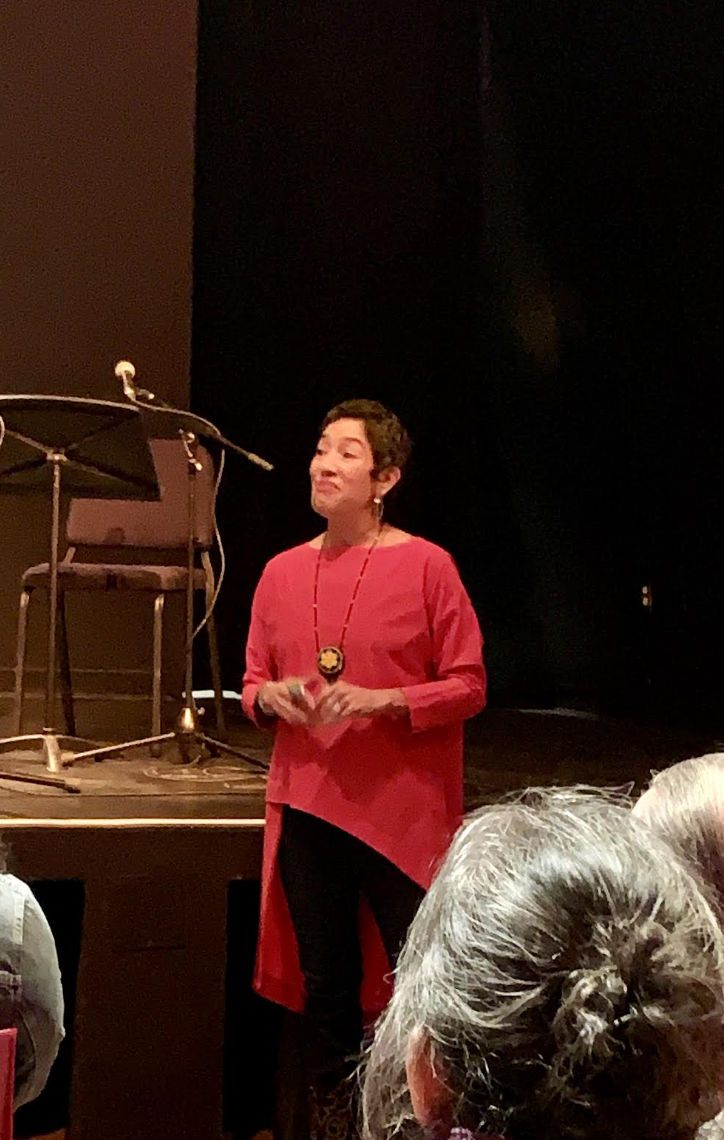

Brian C. Nixon, Ph.D., is Chief Academic Officer and professor at Veritas International University in Albuquerque. As a writer, musician, and artist, his interests surround the philosophical transcendentals: truth, beauty, and goodness.You can contact Brian via his Bandcamp email address: https://briancharlesnixon.bandcamp.com

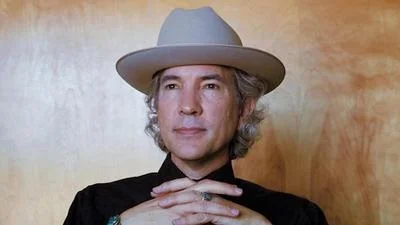

Director, Alicia Lueras Maldonado. Photo by Brian Nixon

Actors, from left: Darryl DeLoach, Katrina Guaraschio, Sandra Marroquin Evans, Kim Nieve Larrichio, Jessica Helen Lopez, Jazz Cuffee, Monica Rodriguez, and Sylvia Sarmiento. Not pictured: Anna Lee. Photo by Brian Nixon

Las ofrendas alter. Photo by Brian Nixon