Guaranteed basic, or universal, income is an idea with deep-seated problems – it is too expensive and could deter people from pursuing educational opportunities and higher wages, according to the head of a Texas-based think tank.

Some New Mexico legislators have floated the idea of such a payment, drawing on a form of the income being introduced in municipalities. State Rep. Javier Martínez (D-Albuquerque) says research is revealing that families can be uplifted by a guaranteed basic income (GBI), government-backed and providing enough for people to cover the basic cost of living and some financial security.

"Now, with regard to cash assistance or guaranteed basic income, the research is coming out," Martínez told Matter of Fact TV with Soledad O'Brien. "I think that we will see, once that research is available, that in fact families have been uplifted, in a very positive and transformational way."

He cited the examples of Stockton and Los Angeles in California, which he said were making "transformative investments in guaranteed basic income."

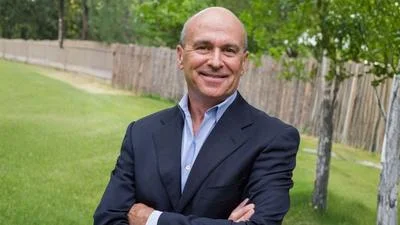

But Charles Blain, president of the Houston-headquartered Urban Reform Institute, a free-market think tank, described GBI as an "old idea that has new life but it still struggles with the same problems as always.

"Implementing a program like this is incredibly expensive and while it might initially be charitably funded, we know that the goal is for supporters to have it government-funded and that carries a high price tag," Blain told the New Mexico Sun. "Aside from the actual cost, there's the social cost that comes with a program like this. Recipients might not feel the urgency to pursue educational opportunities or progressively higher-wage opportunities because it could potentially mean a loss of their GBI funding."

Economists Melissa Kearney of the University of Maryland and Magne Mogstad of the University of Chicago have calculated that introducing GBI across the country would cost $1.2 trillion annually, or 5.9% of total economic output.

In a report in the Wall Street Journal, the economists argue that the amount exceeds what the U.S. government spent on Social Security in 2019.

It would need to be funded by an even greater increase in the existing budget deficit, dramatic increase in taxes, or cuts in spending, Kearney and Mogstad argue.

Blain wrote in a column for the Houston Daily that GBI is limited in its ability to encourage upward mobility.

"Of course, it alleviates immediate burdens from short-term expenses, but doesn’t close gaps in wealth or income disparity," he argued.

In a previous column, Blain pointed out that several municipal policies like excessive land-use regulation, high local taxes and hurdles to new and existing businesses greatly exacerbate cost of living, affordability and income-disparity issues in America's urban centers.

"While GBI is supposed to improve standards of living for those on the lower end of the economic spectrum, as long as local officials continue to further regulate housing, levy burdens on existing and new businesses and increase local taxes, cost of living will continue to increase.

"Economic disparities need to be addressed," Blain continued. "But long-term, sustainable solutions for upward mobility are needed, not policy with good intent that only pacifies a struggling public but continues to handicap generations to come."