New Mexico’s education system has long ranked near the bottom nationally in student achievement, with chronic challenges in literacy, teacher recruitment, and rural access. But behind those statistics is a statewide push to enact structural reforms—from teacher residencies to science-based reading instruction.

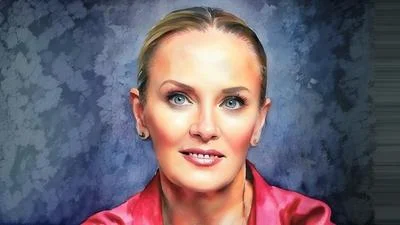

At the center of the effort is Mandi Torrez, a former Teacher of the Year and now education reform director at Think New Mexico, who brings classroom experience and policy insight to the movement. Her approach prioritizes quality teaching, effective school leadership, and long-term professional support as levers to reverse decades of underperformance.

The state education system ranks especially low in fourth-grade reading and eighth-grade math scores. “Those things keep me up at night,” Torrez says, resulting from her passion for education but also by her personal stake as a parent of daughters in the public school system.

But she has a plan. “I don’t think it’s ever too big to solve,” she says, pointing to incremental progress. She highlights Mississippi’s success, where thoughtful reforms led by Dr. Carrie Wright, former education secretary, have yielded results. “She called it the Mississippi Marathon,” Torrez explains, noting that Mississippi’s gains came from deliberate, high-quality efforts rather than rushed implementations.

Mississippi hired expert literacy coaches to support teachers, selecting only 25 out of 150 applicants to ensure top-tier expertise. “They really just focused on we’re not just going to rush into things, we’re going to keep it quality,” she says, suggesting New Mexico could adopt a similar approach.

Torrez identifies two critical in-school factors for improving education: the quality of teachers and principals. “The quality of the teacher right there in front of the kids every single day” is paramount, she says, followed closely by the principal’s leadership.

She acknowledges shortcomings in teacher preparation, particularly in reading instruction. New Mexico is now investing $20 million annually to train teachers in the science of reading, a method proven effective in states like Mississippi.

She commends lawmakers who “really pushed for legislation for all teachers to get trained,” though she adds that many teachers question why this training wasn’t part of their initial education. The state is also addressing Principal training, with new legislation introducing tiered licensure to provide tailored professional development. “That’s going to take some time as our colleges have to figure out what those training programs look like,” she says.

Professional development is a weak point, with Torrez critiquing its often ineffective delivery. “I never once had one that I thought was effective in those few days,” she says of in-service days, suggesting teachers’ time would be better spent planning or reviewing student data. She advocates for sustained coaching over one-off workshops, emphasizing that “every single teacher–I think–could benefit from coaching.”

She says that professional learning communities (PLCs), where teachers collaborate to address classroom challenges, are ideal but often disrupted by competing demands like paperwork or special education meetings. “That’s the ideal situation,” she says, but in many schools, PLCs “fall to the side” due to poor structure or lack of training.

Charter schools, which often outperform traditional public schools in test scores, offer lessons but aren’t a universal solution. “You have some charters that are doing very well, and you have some charters that are struggling,” Torrez says.

She attributes success to innovative practices and strong leadership, noting, “When you have a good school leader, it doesn’t matter if you’re in a charter school or a regular public school, that school is going to thrive.”

However, replicating these successes across all schools remains challenging, partly due to teacher shortages, especially in rural areas. “Our rural districts will try to incentivize things,” she says, citing four-day school weeks as a recruitment tool.

Torrez is spearheading initiatives like the New Mexico Alliance for Teacher Residencies to address teacher quality. Unlike alternative licensure pathways, which allow individuals with any college degree to teach without training, residencies pair aspiring teachers with master educators for hands-on experience.

“You’re not the teacher of record,” she explains, contrasting this with alternative licensure’s sink-or-swim approach. New Mexico’s residency program, which offers a $35,000 stipend, is gaining national attention, though Torrez pushes for better incentives to compete with starting salaries of $55,000 for licensed teachers. “We’re really working on leveling that playing field,” she says.

Class size reduction is another priority, with Torrez advocating for caps at 20 students in early grades. “If you’re not reading by third grade, you’re less likely to graduate from high school,” she warns, citing research linking early literacy to long-term outcomes.

Despite pushback over costs and teacher shortages, she argues, “You’re never going to get more teachers if you don’t change their working conditions.” Torrez also sees potential in community involvement, though she cautions that volunteers, like parents grading papers, can add complexity. “Sometimes managing another adult in the room can be harder,” she says, though small-group support is valuable.

Through Think New Mexico, Torrez engages with legislators during interim sessions to shape policy. “The work is going on right now,” she emphasizes, urging public involvement. Her resolve is clear: “We’re getting some footholds. It is a long climb up, but we’re headed in the right direction.”

The Suncast podcast covers the people, places and policies that make New Mexico the Land of Enchantment and is hosted by Jim Williams. If you’d like to listen to the full episode with him and Mandi Torrez please follow the links at our Federal Newswire Podcast page.