Albuquerque is about to enter a mayoral race where voters are most concerned about crime. Former law-enforcement leaders Mike Geier, Thomas Grover, and Brian McCutcheon say that new policies should emphasize visible policing, and they are pressing candidates to offer practical plans that will restore order on Albuquerque streets.

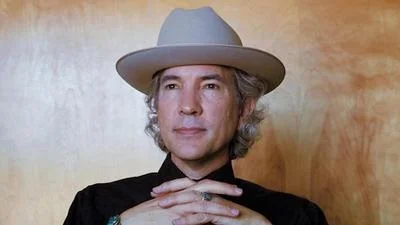

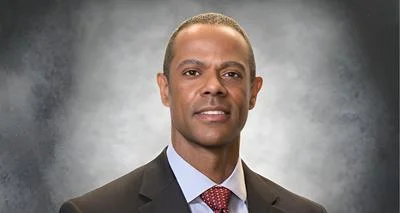

Geier served as Albuquerque’s chief of police from late-2017 to 2020. Grover is a former APD sergeant who now represents officers as an attorney. Brian McCutcheon is a former APD officer who helped secure the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta and now directs safety and security at Calvary Church.

According to Geier, the current administration did not keep its promises. “The mayor said it was his responsibility to reduce crime, and he promised more APD officers—1,200 was the target,” he says. “Later he said it was ‘fantasyland’ to believe that could happen.”

McCutcheon says low-level offenses are the gateway to larger crimes. “Get boots on the ground addressing shoplifting and the rest, or you invite the higher-level crimes.” He questions City Hall’s statistics. “The mayor said we had an 11% auto-theft reduction. Insurance data for Albuquerque showed 8%. Somehow there was 3% misreported, and he capitalized on that.”

Grover describes why police officers have left the force. “People became police because it was a calling,” he says. “If leadership did not inspire, they looked elsewhere.” He says that politicized discipline hammered the wrong people. “Good officers were crucified for administrative slips while protected species could do no wrong–it became a betrayal of trust.” The climate in the field, he adds, feels threatening. “Officers face higher resistance and more combative behavior. It is probably more dangerous to be a police officer now than it has been for decades.”

Staffing and deployment are the biggest issue facing the police department, according to them. Geier says the city needs more officers on patrol. “You can drive 20 or 30 minutes through busy areas and not see a police unit,” he says. “Get people out of niches and onto the street. Use directed patrol where the data said crime hit, rotate the times, and you change behavior.” McCutcheon says practical levers are to “eliminate administrative bloat, put power back in sergeants’ hands, recruit hard in the military, at colleges, and across state lines.”

Other policy shifts have also hurt the force. For example, they see the Department of Justice’s court-approved settlement agreement as a mixed legacy that drained street staffing. “We went from a small unit to dozens in a use-of-force division while field numbers shrank,” Geier says. McCutcheon points to fallout. “They tried to make a new policy retroactive on SWAT,” he says. “The team walked, and years of experience vanished in an instant.”

Juvenile crime trends worry them, and McCutcheon says social media glamorizes offenses. “You see kids posting robberies and break-ins as trophies,” he says. He cites a surge since 2020, adding that “forty percent of the carjackings are juveniles between 11 and 17.” Grover says policy must reflect real accountability. “The rules the courts follow come from the legislature.” In his view, “the buck stops there.”

The three former law enforcement officials provide a voter checklist for candidates. Grover starts with culture. “Get politics out of law enforcement,” he says. “Choose a chief who inspires from the front, engages cadets and supervisors, and carries a record of real success.” Geier zeros in on operations. “Put more marked units on the street, measure quality outcomes instead of paper numbers, and use the Real Time Crime Center to drive daily deployments,” he says. McCutcheon pushes for scale and urgency. “Aim for 1,700 officers,” he says. “Recruit everywhere, empower supervisors, and let cops do police work.”