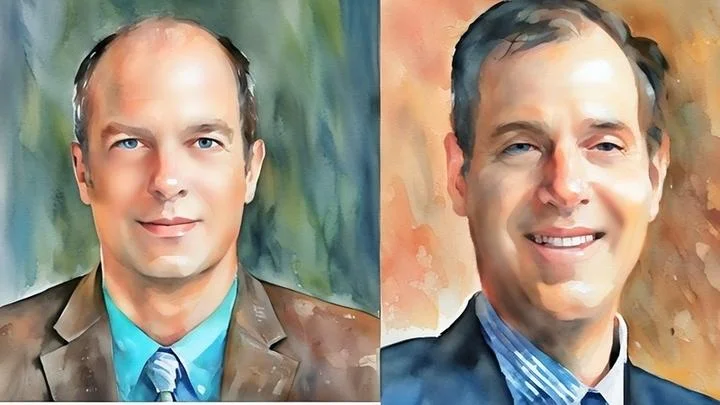

Many health practitioners fear that New Mexico’s health system is becoming too fragile because of high malpractice costs. Without reform, Fred Nathan, attorney and founder of Think New Mexico, and Paul Gessing, president of the Rio Grande Foundation, fear that more physicians will retire early or relocate to states with fairer systems.

Nathan advocates for pragmatic policy changes and says malpractice reform is not about attacking lawyers. “It might even help their business,” he says, as lawyers from other states move into New Mexico because of the current system. He adds that “some trial lawyers are very resentful and wouldn’t mind a little bit of reform.” He also notes that states like California cap attorney’s fees in malpractice cases, while New Mexico has no limits at all. “What we’re proposing is not partisan,” he says. “It’s something that’s accepted in other states on both sides of the aisle.”

Gessing agrees the legislature has a responsibility to act. “The legislature in New Mexico is quite powerful,” he says. It should focus on retaining physicians and bringing down costs. “Medical malpractice reform is one of those ways,” he says. But, according to him, entrenched interests slow progress. “Trial attorneys are part of the three-legged stool of the Democratic Party’s fundraising and political base, alongside unions and environmental groups.”

Nathan says the costs are staggering and points to Rehoboth McKinley Christian Health Care Services. “In 2024, they paid $1.2 million for $30 million in coverage. In 2025, $1.4 million for $14 million. In 2026, they anticipate $1.8 million for $6 million in coverage.” That trajectory, he says, will make it impossible for hospitals to operate. Patients also suffer because attorney’s fees cut into awards. “If the attorneys are paid a higher percentage, like 40%, that’s less available to the patient–who’s the client–to make them whole.”

Specialists are among the hardest hit under malpractice costs, according to Nathan. “A neurosurgeon leaves New Mexico for Arizona and pays one fifth of what he pays in Albuquerque,” he says. He recalls OBGYN Debbie Vigil’s decision to retire early after the legislature raised damage caps. She said she did not want to pay money to practice medicine, and that she adored her patients. “I hated doing this, but I had no other option,” she said, according to Nathan.

Reformers also battle lobbying groups, and Gessing says a group called “New Mexico Safety Over Profit” is the lead opponent. The group is “almost entirely trial lawyers,” according to Gessing. “They raised and spent about $1.3 million to stop reforms.” He adds that the State Ethics Commission forced the group to disclose its donors, “and not a single donor was a patient–this was just really a dark money front group for the trial lawyers.”

Nathan and Gessing believe solutions exist and point to California’s model. “They cap attorney’s fees at 25% if the case is settled and 33-and-one-third if it goes to trial.” Gessing says New Mexico should emulate that example. “New Mexico could actually benefit from following them in this particular case,” he says.