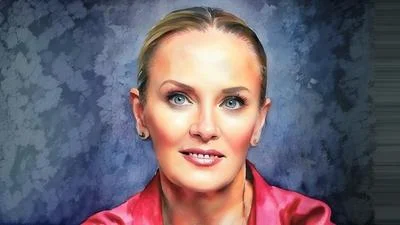

Reintroduction of the Mexican gray wolf to New Mexico in 1998 created one of the state’s most divisive wildlife issues. Senator Crystal Brantley, who represents District 35 in the southwest corner of the state, says the controversy is about more than wildlife—it is about protecting families, safeguarding livelihoods, and rethinking federal management.

Brantley’s district covers rural New Mexico, including Sierra and Catron counties, where most of the state’s wolves roam. Before entering the legislature, she built her career in agriculture and community leadership, bringing those perspectives to Santa Fe. Her political work now blends firsthand knowledge of ranching life with advocacy for policies she says are necessary to preserve both economic stability and public safety.

“My Senate district encompasses rural New Mexico—seven counties in the southwest,” she says. Brantley raises her young daughters on her family ranch among wolves, so sees the challenges resulting from wolves in the area firsthand. “The personal safety of your children is a priority above cattle any day,” she says.

The wolf reintroduction program was controversial from the start. “On one side, we have radical environmentalists that say wolves belong,” Brantley says, “and on the other side, we have to figure out how to raise cattle and raise families.”

Catron County is the epicenter. “Eighty-five percent of the Mexican gray wolves in New Mexico are in Catron County alone,” Brantley says. The losses, according to her, ripple through the economy. Tourism during the hunting industry is the top economic producer in Catron County, followed by ranching. “The introduction of the Mexican gray wolf is taking an absolute toll on both because they eat and they eat a lot… It's either elk or it’s livestock,” Brantley says.

In her view, wolf deterrents and reimbursement programs for lost cattle have done little to solve the conflict. “Response time is very slow… it is very difficult to get confirmed kills from wolves because the carcasses are often never found.” With vast, mixed-ownership landscapes, proving wolf depredation is impossible.

Local leaders are calling for action. “Catron County declares a state of emergency, and there are 14 other counties that pass resolutions in support,” Brantley says. Schools have to protect children as well. “Catron County develops wolf-proof bus stops. Children waiting for the bus are now in wolf-proof cages.”

According to her, federal management makes wolves more dangerous. “These wolves are cage-raised, vaccinated, collared … and it comes at a cost of about $1 million per year per wolf,” she says. “Over time, these wolves become habituated and quite familiar with human presence, and that’s where the problem lies.” She recounts a female wolf bedding down in her daughters’ playhouse during a snowstorm and another circling her car as her child cried in the backseat.

Momentum in Congress may soon shift how this program operates. Currently under the federal Endangered Species Act, virtually no action can be taken to remove wolves or even protect against them. Ranchers and others face stiff fines and worse if they are found to have harmed the protected species.

“Representative Gosar introduced a bill that would delist the Mexican gray wolf, and we expect that bill may get some traction,” Brantley says. If delisted, she expects state agencies to take over.

But questions remain. “What happens the day after delisting when there is a wolf reported on the grounds of Reserve High School?” Brantley asks. “There are big unknowns.” Still, she calls efforts to de-list the wolf from the list of endangered species or other efforts to protect against wolves “a big win for New Mexico cattle ranchers.“ Her strong preference is to place authority for wolf management at the local level where the right balances can be found, “We can handle it ourselves,” Brantley says.