For decades, Alaska Native Tribes have fought to protect their rights to subsistence fishing, a practice essential for their communities. The ongoing legal battle centers on who controls fishing access and regulations on Alaska’s rivers, with Tribal Nations facing competition from commercial, sport, and personal use fisheries.

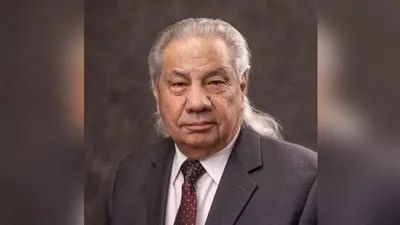

Katie John, an Ahtna Athabaskan Indian and daughter of the last chief of Batzulnetas, became a key figure in this fight. Represented by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), she challenged state-imposed restrictions that closed subsistence fishing along the upper Copper River after Alaska became a state in 1959. Her efforts led to a series of court cases known as the Katie John trilogy.

In 1980, Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), creating conservation system units managed by the federal government and establishing a priority for rural subsistence hunting and fishing on federal public lands during shortages. This priority was intended to safeguard traditional practices vital to Alaska Natives’ existence.

The State of Alaska did not implement its own enduring rural subsistence priority as required under ANILCA. As a result, federal agencies formed the Federal Subsistence Board in 1990 to manage these resources. The board includes members representing rural users.

A major point of contention has been whether navigable waters—rivers large enough for travel—fall under federal or state management. While the state claims authority over these waterways because it owns the land beneath them, courts have repeatedly ruled that ANILCA’s protections extend to navigable waters within or alongside federal lands.

This issue resurfaced after the 2019 Supreme Court decision in Sturgeon v. Frost, which limited National Park Service regulation over certain river uses but did not overturn prior rulings protecting subsistence rights. However, following this case, Alaska began arguing that Sturgeon had effectively invalidated earlier decisions favoring rural subsistence priorities.

In recent years, declining salmon populations prompted emergency closures of rivers like the Kuskokwim by federal authorities. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service allowed limited openings for federally qualified rural residents; meanwhile, Alaska opened these periods to all Alaskans regardless of residency or reliance on local fish stocks.

The conflict led to litigation when the federal government sued Alaska for issuing conflicting regulations they argued violated ANILCA’s provisions. NARF intervened on behalf of Tribal organizations and individual fishers supporting rural priorities.

In August 2025, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reaffirmed previous decisions supporting federal management and upheld Title VIII’s protections for rural subsistence users: “Although Katie John, the Ahtna woman who advocated for subsistence fishing rights on behalf of Alaska Natives, has since passed away, the precedent that bears her name lives on,” wrote Judge Callahan.

Alaska is now seeking Supreme Court review in hopes of overturning this decision while salmon populations continue to decline—a crisis affecting many dependent communities.