Commander Kyle Hartsock, a 21-year veteran of New Mexico law enforcement, currently serves with the Criminal Investigations Division of the Albuquerque Police Department.

Raised in the South Valley and the son of a truck driver and Forest Service worker, Hartsock didn’t come from a law enforcement family. He joined the force after watching Cops and Law & Order, passing a test with the Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office at 19.

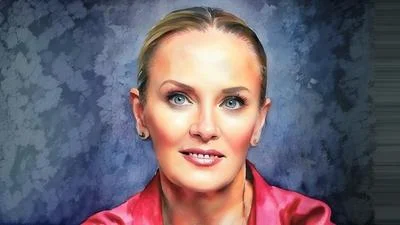

Shelley Repp, meanwhile, is the executive director of the New Mexico Dream Center, a nonprofit that provides aftercare for survivors of human trafficking. Repp has spent years working with exploited youth and has even adopted a trafficking survivor herself.

Together, Hartsock and Repp form a powerful alliance between law enforcement and community care, driven by the belief that every person deserves to feel safe and seen.

A major focus of Hartsock’s work is combating human trafficking, particularly among minors. He helped create the Ghost Unit at BCSO, a program that targets runaway and “throwaway” youth through a victim-centered approach. “There was no guidebook,” Hartsock says. “We had to learn from our victims. Our victims became our teachers.”

One of those victims—a 15-year-old girl locked up for prostitution—helped shape his entire philosophy. “Even when she cried out for help, a lot of adults weren’t giving her any credibility,” he recalls. “She was calling police. She was making statements. She was getting these nurse examinations done, and no one wanted to listen to her.”

Hartsock and his colleagues realized that law enforcement had been mislabeling these young people. “We call them deviant behavior juveniles. We call them alcoholics. We call them drug addicts. We call them runaways. In reality, most of them are victims,” he says.

The Ghost Unit’s name is meant to reflect how invisible these kids have been to society: “They are all around us, and we just don’t see them.”

He works closely with community advocates like Repp, who has known Hartsock for years. “What they were doing was unique,” Repp says. “They developed this very specific unit… not just to look for [victims] and bring them in, but to look at it through a victim’s perspective, through developing relationship. Relationship can be just these really powerful tools.”

New Mexico's youth homelessness crisis is significant. Repp cites a 2021 report estimating at least 1,264 unaccompanied minors on the streets—a number likely twice as high in reality. Many are never reported missing. “Where’s a runaway? Somebody who is reported as missing. But these kids—throwaways—nobody’s looking for them,” Repp says. That invisibility makes them extremely vulnerable to trafficking.

Hartsock shares one way they work to reach these kids. “Every time we find a runaway, we’d say, ‘Hey, where do you want to live?’ It was this really empowering question they’ve never really gotten asked,” he says.

In one case, they arranged for a runaway to live with her boyfriend’s mother—someone who cared about her and agreed to take on parental responsibilities. “Now we just got credibility with her. She now feels... this police department actually wants maybe what’s best for me.”

Credibility and trust open the door to deeper conversations, including about traffickers. “It started on a victim-centered model of trust and credibility. But we had to be genuine. You can’t fake it,” Hartsock says.

Despite the trauma inherent in his work, Hartsock remains grounded through his family. “What better motivation and inspiration to have than my family, especially my kids?” he says. “At this point in my life, I’m living for their memories.”

As the father of ten, he sees parenting itself as a form of prevention. “What Kyle does is he makes choices... to have that good relationship, because that is a protective factor,” Repp says.

Still, Hartsock is realistic about the challenges. “There’s not a law enforcement officer out there who believes we can solve this alone,” he says.

Public engagement and nonprofit partnerships are critical. Organizations like the Dream Center provide aftercare and stability. “We just can’t [do this alone],” Hartsock says. “We have to have a place to bring the child to… it needs to feel like, ‘Hey, this is a safe place for me.’”

He’s also candid about the complexities of criminal behavior. “The amount of people that I would call truly through-and-through evil that I’ve interacted with in 21 years, I could count on one hand,” he says.

Most offenders are opportunists shaped by similar childhood trauma as their victims. “You look at their childhoods—a lot of them are just like your victims’ childhoods. They look identical.”

Technology has added new threats. “Anybody can be anybody behind a screen,” Repp says. Traffickers use social media, gaming chats, and other platforms to exploit youth. Hartsock describes sting operations where officers pose as minors. “Except when you show up, it’s handcuffs and booking paperwork.”

His message to lawmakers is clear: New Mexico needs more resources—more shelters, more rehab beds, more transitional housing. “Everyone needs a home to go to to feel safe,” he says. “We’re going to pay for that person our whole life, one way or another. Is it the prison? Is it the funeral? Or is it a stable living environment when they’re 14, 15, 16?”

For Hartsock and Repp, it all comes back to the same mission: keeping people safe and giving kids the chance to feel seen. “We all strive for connection,” Hartsock says. “Someone who really cares and makes that person feel loved is really important. And that’s missing in so many families.”