Though Democrats and Republicans in the House of Representatives joined forces to quash a Paid Family Medical Leave bill, that doesn’t mean the door is closed on more far-sighted legislation, a legislator suggests.

The rejected program offered to pay workers for up to 12 weeks of medical or family leave necessitated by their individual or family needs. Yet among drawbacks leading to the bills' demise, burdening employers with a share of the costs triggered strong opposition from the New Mexico Business Coalition (NMBC) in defense of businesses already crushed by COVID.

“After the devastating COVID lockdown, this is a cost many employers are unwilling to pay,” NMBC reports in a website cost analysis. “Many have said they would leave the state if PFML passes in New Mexico.”

Though House Bill 6 and Senate Bill 3 inspired hours of debate in both chambers, the fatal stroke came on Feb. 14 when 11 House Democrats joined every Republican in a slim 34-36 defeat, according to the official roll call. Conversely, only one Democrat had voted against its counterpart when it gained approval 25-15 on Feb. 9, Source NM reported. Democrats shared several concerns, including whether this would be a budgetary flop and how state-funded entities serving vulnerable populations would fare.

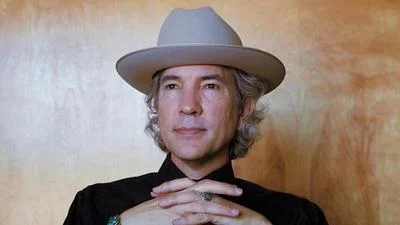

Among those who voted against HB6, State Representative Marian Matthews (D-Albuquerque) detailed some of the bill’s fatal flaws and gave her stand on PFML in general.

“I did not support the SB3/HB6 Paid Family Medical Leave bill. However, I believe the concept of PFML is a good one: a time for a family with a new child to bond with the child, some additional time off for those helping to care for a loved one with a serious illness or their own serious illness,” Matthews told New Mexico Sun. “It is essentially like a short-term disability insurance policy. I sponsored HB11, which offered an alternative structure for a PFML program.”

One of problems she cited is that the crafters of HB6 and SB3 failed to include certain key groups in their formulative discussions.

“Health-care providers, childcare providers and the providers of caretaker services were not ‘at the table’ despite the fact that such organizations had volunteered to serve on the task force designing the program. There was limited rural New Mexico representation,” she said.

Matthews described how those bills carried negative consequences for businesses and other groups. “SB3 did not, in my view, work for all New Mexicans. It would have had negative consequences for those who require caretaker services—the disabled, those with special needs and the elderly, particularly the frail elderly—and the caretaker organizations which provide those services,” she said.

“SB3 created an unfunded government mandate for these organizations.”

Small businesses also stood to suffer as well as childcare providers, health-care providers and those having to meet certain state requirements like staff-client ratios, she told New Mexico News. “Filling these vacancies in a very tight labor market for 12-week periods would likely have been very difficult and might have caused a reduction of services in childcare, health care and similar services,” she said, all filling a “critical” need.

Additionally, the defeated PFML bills raised funding concerns. As Matthews explained, “In SB3, PFML would have been funded by a payroll tax on workers’ wages and by a tax on employers’ total payroll.”

According to NMBC’s cost analysis, the impact on employers would have been .004 of every dollar paid to every employee, or $4 per $1,000. The impact on workers was estimated at .005 of every dollar earned or $5 per $1,000. For a full-time worker paid $17.51 hourly, it would have meant a $182 annual hit, with their employer’s share estimated at $145.68 a year. Higher salaries and more employees would deepen this impact.

Yet the financial toll didn’t stop there. Matthews said there’d be start-up costs, some of which were to take the form of a loan. Despite costs to businesses, workers and the state, she said, “No actuarial studies were run to determine whether the program was likely to be solvent.” She notes that states with active PFML programs are among the nation’s wealthiest 25, while New Mexico would have had the lone PFML program among the poorest five states.

Even the administration of the program by DWS drew questions. “It was estimated that DWS would have had to employ some 200 additional workers to administer PFML,” she said, citing DWS’ 20% vacancy rate, struggles with $250 million in fraudulent claims during COVID as well as many failures to meet program deadlines and goals.

As an alternative, Matthews’ bill “suggested that PFML be administratively attached to DWS in order to have access to the payroll records DWS maintains, but that an independent board actually run the program.”

Matthews was also asked about negotiations to fix the flaws she cited with HB6 and SB3. In response, she said, “HB11 was itself an effort to negotiate with the sponsors of SB3/HB6 by offering alternative proposals for a PFML program.” This was in harmony with input gained in November 2023 at a policy institute on PFML at Vanderbilt University, which Matthews and the bills’ sponsors attended.

“Presumably there will continue to be interest by various legislators and groups to enact a PFML bill. The results of the 2024 elections may impact the future of PFML and the content of a PFML bill,” said Matthews, looking ahead.

Matthews has served on the House of Representatives since 2020 representing District 27 in Albuquerque's Northeast Heights, but her public service spans at least three decades including time as assistant attorney general. According to her bio, Matthews has a record of advocating for consumer protection and elder rights by drawing upon her extensive legal experience.